Lauren Shaffer, OWLA Executive Recorder and Editor of The Cardinal

Spanish Teacher, Dalton High School

“Profe, I think my Spanish is getting worse.”

I have heard this from multiple students over the years, and actually felt like this myself at one point in my language learning journey. I remember feeling like I needed to start over at the beginning; I was aware of gaps in my knowledge and I desired to fill them. Little did I know that this feeling was a good sign. It meant that I actually knew more than I realized, and I was more competent than I believed myself to be. Psychologists call this phenomenon the Dunning-Kruger Effect (Kruger & Dunning, 1999).

The Dunning-Kruger Effect is a cognitive bias where people with limited knowledge in an area tend to overestimate their own competence because they are unaware of just how much they don’t know (Kruger & Dunning, 1999). As their knowledge increases, they become more aware of the complexity of the topic and may begin to notice gaps in their understanding. This new awareness may cause them to doubt their abilities, even though their actual competence is increasing.

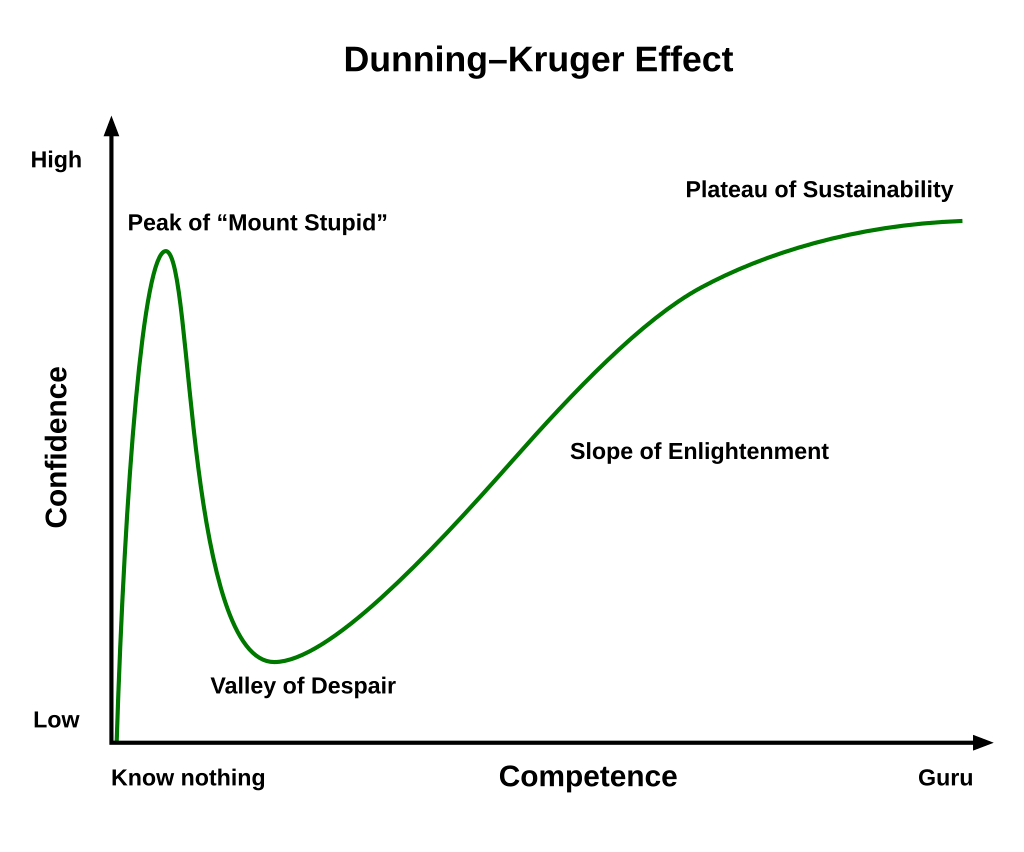

Although not part of the original research, the Dunning-Kruger Effect is often illustrated through this visual representation that maps confidence against competence (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dunning-Kruger Effect graph. Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons by Wikimedia Commons contributors (n.d.), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dunning%E2%80%93Kruger_Effect_01.svg

When I first learned of the Dunning-Kruger Effect, I immediately equated it to what my students experience when learning Spanish. They come to me for the first time from their Spanish I classes bright-eyed and feeling good about their Spanish. The students, according to the popular visual representation, are unknowingly at “The Peak of Mount Stupid.” As we near the end of Spanish II, some students start to comment on how they feel like their Spanish is actually getting worse; we have hit the “Valley of Despair!” Students are suddenly realizing that the language is more complex than they first believed, and feel that they’ll never make it out of this pit.

In my mind, this drop in confidence reflects students’ transition from the novice level to the intermediate level. Novice learners depend mostly on a limited amount of memorized language, which is relatively straightforward. The language of novice learners is known to be fairly accurate because it is simply a recall of memorized phrases. At the intermediate level, students begin to create with language. Suddenly they have to make more decisions. They may begin thinking about smaller nuances in word choice, syntax, verb tense, etc., all of which make language production more complex and increase the likelihood of errors. And as teachers, we see these errors. The language of intermediate learners can be messy, although their ability to create with language is much greater than it was at the novice level.

It’s frustrating for students to feel like they’re getting worse. As soon as I begin to hear these kinds of comments, I share the Dunning-Kruger effect with my students. I assure them that what they are feeling is very normal and encourage them that with continued practice, they will come out of this. As great as it felt to be perched at the top of “The Peak of Mount Stupid,” it’s much better to be deep in the “Valley of Despair” because it shows that they are progressing.

As we consider how the Dunning-Kruger Effect applies to language learners, here are some practical reminders:

- Trust the process of language learning. Learning a language takes time, developing gradually through engaging with meaningful input. While it may feel that we can speed things up through explicit instruction, it has little impact on true acquisition.

- Normalize errors as part of learning. Our goal should be to lower the affective filter and make students feel comfortable taking risks with the language. Placing too much emphasis on errors or constant error correction may shut students’ language production down.

- Focus on quantity and complexity over grammatical accuracy. Because grammatical errors are common in the language of intermediate learners, it is unfair to hold students to high standards of accuracy. Focusing on quantity and complexity highlights students’ growth rather than drawing attention to their weaknesses.

- Celebrate students’ language. It’s important to demonstrate enthusiasm for learners’ language skills the same way we celebrate a child’s first words in their native language.

Unfortunately, there is no shortcut out of the Valley of Despair. As teachers, we should strive to create a supportive environment where we help students navigate these challenges and stay motivated. By focusing on what students can do rather than what they cannot, recognizing their progress, and celebrating their successes, we can help them to find the confidence needed to continue growing as language learners.

References:

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

Wikimedia Commons contributors. (n.d.). Dunning–Kruger Effect 01 [SVG image]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dunning%E2%80%93Kruger_Effect_01.svg